Photo Blind, Valentine National Wildlife Refuge, NE

The Valentine National Wildlife Refuge encompasses the largest remaining mid- and tall-grass prairie tracts in North America. It was established in 1935 and is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Along with Fort Niobrara and the John and Louise Seier National Wildlife Refuges, they form the Fort Niobrara National Wildlife Refuge Complex.

The refuge has two viewing blinds, positioned annually within close proximity to booming grounds for the Greater Prairie Chicken and the Sharp-tailed Grouse. A booming ground, or lek, is an area where these species perform their nuptial displays accompanied by species specific booming and drumming sounds produced by the movement of air through their wings.

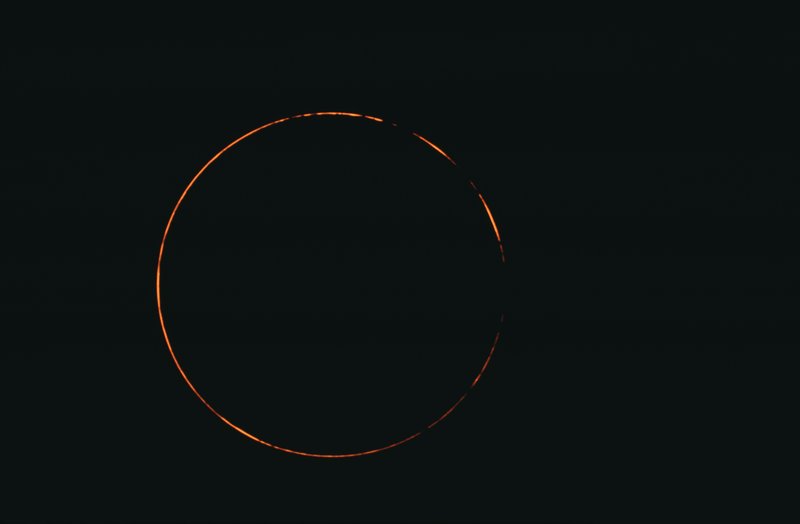

Since I had to be at the refuge by 4 a.m. anyway, it made sense to go earlier to photograph the Milky Way moving across the southern sky above the prairie and my blind. Both the inside and outside of the blind are lit, but other than that, it really looks like that.

Dark Skies

Because of my background in photojournalism, I am often asked whether I believe there is a “decisive moment” in landscape and wildlife photography. For those who don’t know, the concept of the “decisive moment” was made famous by the late, great Henri Cartier-Bresson, who said, “There is nothing in this world that does not have a decisive moment.” In his words (and spellings), he wrote, “Photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organisation of forms which give that event its proper expression.”

My positive response to the question lies in the second half of his answer as composition is a critical element in all genres of photography. One difference between news photojournalism and environmental photography is contained in the famous photojournalism cliché “F8 and be there" often attributed to Arthur Fellis (WeeGee), the noted street photographer in New York circa 1930s & 40s. This philosophy is often echoed by my colleagues in the Natural Arch and Bridge Society when asked, “When is the best time of day to photograph a natural arch?” and their response, “When you are there.”

Of course, it is infinitely more complex than that response, which is always delivered with a smile, and to me, that complexity involves light. That is the commonality found in this grouping of photographs that depend on light more than anything else. Although there are not any photographs of sunrises or sunsets included, there are photographs that include the sun and the moon, sometimes even in the same photograph, and other photographs that rely on the first and last rays of morning and evening sunlight, reflected light and the rising and setting of the moon as a focal point of interest.

My best advice? Get up early, stay up late and nap in between.